1. The Structure of the US Government

American systems of governance were built on the notion that government representatives (lawmakers) are meant to represent the interests of the populations they serve. Americans vote for elected officials, and they rely on them to work towards society’s collective goals. But to optimally represent the interests and goals of a community, representatives need to know what they are. This is where legislative advocacy comes in, offering the opportunity to frame the public policies of cities, states, and nations.

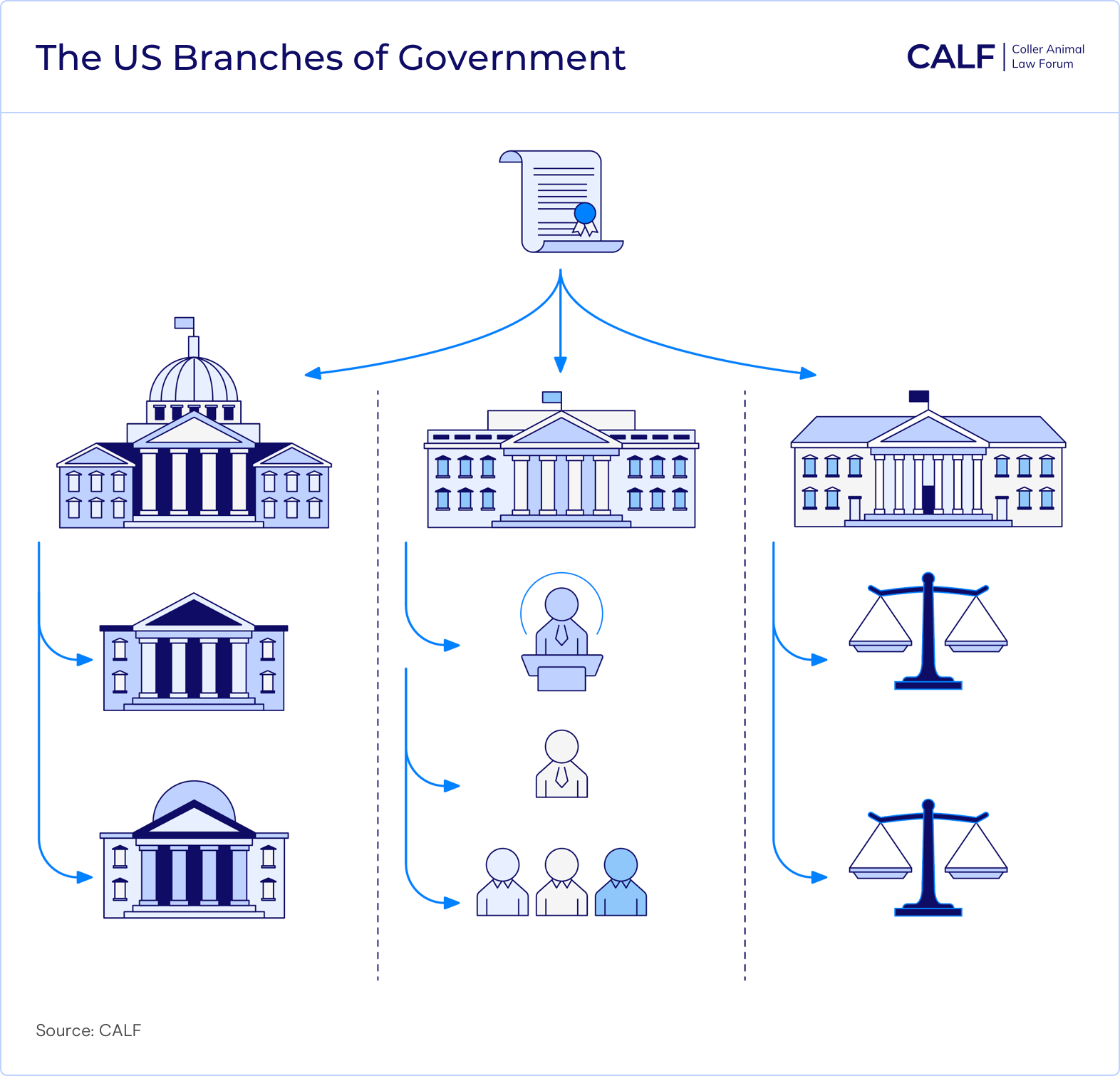

1.1. The Three Branches of Government at Federal Level

As the elements of legislative advocacy are explored in this resource, the focus is on the legislative branch of government. U.S. governmental structures are typically comprised of three branches: the legislative, executive, and judicial branches. These three branches have distinct duties, but collectively provide a system of checks and balances so that no single branch abuses its power. The legislative branch consists of local, state, and federal legislative bodies made up of elected representatives known as legislators or lawmakers. (At the local level, they may be called city councillors or other names.) Legislators assess matters brought to them, or introduced by legislators themselves, and vote on legislation that then becomes law. Except for the state of Nebraska, all states and the federal government have bicameral legislatures where two chambers, known as the House of Representatives and Senate, are responsible for making laws. State senates are the smaller chamber whose members serve longer terms, usually four years. The House of Representatives is the larger chamber whose members serve shorter terms, usually two years. The House of Representatives is called different names depending on the state, for example the Assembly or House of Delegates.

Even though the executive and judicial branches will not be discussed in depth, they each hold remarkable power and serve crucial functions in our systems of governance. On the federal level, the executive branch is made up of the President and accompanying advisors, departments, and agencies. The President is a single person elected by the people to enforce the laws of the land, write executive orders, appoint leaders of federal agencies, and sign legislation into law or veto proposed laws. On the state level, the executive branch is led by a governor, whose duties mirror that of the President (with some notable differences).

The judiciary operates largely independently and is tasked with assessing the legality of the language and enforcement of the laws passed by the legislative branch and executed by the executive branch. Unlike the executive and legislative branches, whose members are elected by the American people, members of the federal judiciary are appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. Selection of judges in the state court systems varies by state, with judges chosen via election or appointment. Generally speaking, judges in the judicial branch interpret the law and determine its proper application and constitutionality. The federal U.S. Supreme Court is the highest and most powerful court in the U.S., with every other American court constrained by the decisions of the Supreme Court. This means that once the Supreme Court interprets a law, lower courts are legally bound by that interpretation and must apply it to particular cases accordingly. This structure is the same in state courts, with lower level courts having to follow the precedents set by higher level courts in the same jurisdiction. The nuances of the judicial process vary by court, but all courts play vital roles in the judicial process of interpreting and applying laws (including laws that advocates might end up passing). Though the judicial system is not the focus of this resource, it is useful to have a sense of how judges read and interpret laws in order to effectively write and advocate for laws that will more easily survive judicial scrutiny.

1.1.2. Local Governments

Local governments are much more diverse in their composition than federal or state governments. The term “municipal government” includes cities, towns, villages, and boroughs that are typically organised by geography and population size. Some of the bigger municipalities in the U.S. have millions of residents, like Los Angeles and New York City, whereas others can have a mere few hundred residents, like Jenkin, Minnesota. These local governments can be created through direct state action, such as developing a state charter, or through state statutes that authorise the formation of local government bodies. Municipal governments provide essential services like police and fire departments, emergency medical services, transportation, and public works (e.g., paving of streets, removing snow, and treating sewage). There are five major types of municipal governments, including mayor-council, council-manager, commission, town meeting, and representative town meeting. The mayor-council structure features an elected executive representative, known as the mayor, with the legislative body known as the city council. Town meeting systems, in contrast, allow qualified voters to congregate, debate, and vote on policy decisions in a more communal manner. Too many local government systems exist to examine each one thoroughly, so those interested in doing legislative advocacy on the local level should start by researching their own government system.

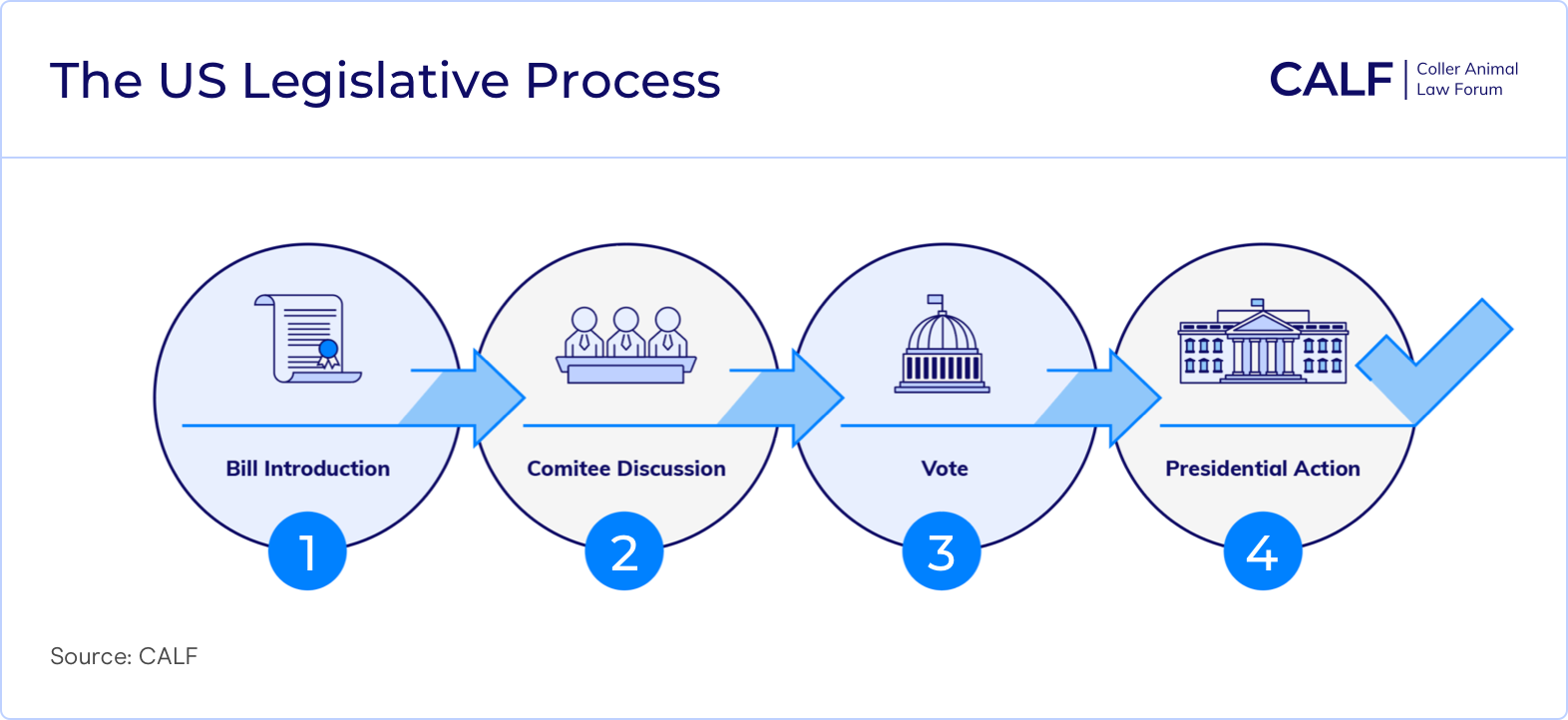

2. The Legislative Process: How Does a Bill Become a Law

Arguably, the most important process to understand when it comes to legislative advocacy is how a bill becomes a law. An advocate might be pursuing the passage of a bill, ordinance, resolution, ballot initiative, or other legislative mechanism, depending on the level of government they are working in. Each of these legislative tools are unique and are enacted into law in different ways. For sake of simplicity, let's focus on how a bill becomes a law on the state or federal level. Advocates can play a crucial part in passing legislation by contacting legislators, proposing ideas for legislation, and asking them to pass that legislation into law. They may have a draft bill or ask state or federal legislators to create a bill that alleviates or solves the identified problem. A political representative who introduces a bill is known as a sponsor—these are allies in helping champion a legislative idea. Other legislators who want to express their support for a bill can officially sign on as cosponsors, which will elevate the momentum of the bill. Once the bill is introduced in either the Senate or House of Representatives, it is assigned to a committee. The committee studies the bill, sometimes has official readings, and decides whether to put the bill up for a vote, a debate, or amendment. If the bill passes out of committee it goes to the sponsoring chamber (Senate or House). If it is successful in the first chamber, it moves to the other chamber. In the other chamber, the bill is assigned to another committee, where the committee process happens yet again. Sometimes this process happens at the same time when there are Senate and House versions of the same bill. Once both chambers agree on a version of the bill and provide final approval, the executive branch (the President or governor) has the option to either veto the bill or sign it into law. There is a lot more to this process than the description provided here, but this explanation should provide the foundation needed to understand the path of a proposed bill becoming an enacted law. Most state websites have additional information about their specific process.

This introductory section supplies legislative advocates with a broad overview of the foundational terms and systems they must know to be successful. It is also important to highlight the value of such advocacy. In a democratic system of government, advocates and citizens can and should remind elected officials how they can best represent the people and their interests. It is impossible for politicians to prioritise the needs and desires of every constituent, so the more advocates make their voices heard, the better chance their needs and desires will be fulfilled. Additionally, by educating legislators, advocates can also educate the public and gain support on issues that might be unfairly overlooked.

3. Legislative Advocacy in the Federal Government

Advocating for federal legislation entails leveraging power as a constituent of the U.S. to influence the lawmaking process. Luckily, advocates do not have to live in Washington D.C. to affect laws and policy at the federal level. But before attempting to make change through federal legislative advocacy, it is important to know some basic information.

The two chambers in the federal legislature are the Senate and House of Representatives, collectively known as Congress (although sometimes the House of Representatives alone is referred to as “Congress”). Every state has two Senators, with the Senate comprising 100 Senators total. There are 435 House of Representatives members, with the size of each state determining the number of members allotted per state. For instance, California has the most representatives (53), Oregon has significantly fewer (6), and seven states have only one representative. Because there is extensive overlap in form and function between state and federal governments, and this resource covers state and local legislative advocacy in more depth, this section will not delve deep into the federal legislative process itself. Rather, this section will feature important considerations for anyone interested in engaging in legislative advocacy in the U.S. federal government.

3.1. Preemption

Before pursuing a legislative campaign, advocates should survey all relevant jurisdictions for issues of preemption. Preemption is a legal doctrine that describes the ability of a higher form of government to confine or eliminate a lower level of government’s power to regulate a particular issue. The U.S. Constitution dictates that federal law preempts state and local law, while state law similarly takes precedence over local laws. Preemption can result in the federal government prohibiting state and local governments from passing laws that are less protective, or more protective, than the higher-level law. It can also mean that state or local governments are prohibited from passing any laws on a particular issue, even if there is no higher-level law overseeing that issue currently. Preemption can be express, where a law explicitly states that lower-level lawmakers are preempted in some capacity. Preemption can also be implied, where the law itself contains nothing explicitly about preemption, but courts or legislatures have found state or local authority to be preempted. For instance, in 2012, the US Supreme Court ruled that the Federal Meat Inspection Act preempted the 2008 Downed Animal Law, which banned the slaughter of non-ambulatory pigs. If the piece of legislation you are working on is preempted by a higher-level lawmaking body, it is best to shift gears and find a new legislative strategy.

No matter what government system you are navigating for your legislative campaign, research the authority of the jurisdiction as contoured by the relevant constitutions and statutes. On the local level, your city government may only have limited powers explicitly granted to them by their state legislature, meaning they may not have the authority to help with the proposed legislative idea in the first place. Other local governments have what is known as home rule authority, where municipal governments can enact laws with less interference from higher authorities. From there, conduct a survey of the laws in the higher-level jurisdictions. Are there any federal or state laws that address the topic or explicitly preempt state or local laws? This task is simpler said than done, as even legal experts may struggle to determine whether there is an implied preemption issue at stake. If you are unable to find proof of express or implied preemption for your topic area, you must decide how much risk you are willing to take to continue with the campaign in the face of potential preemption. Advocates with the means and access should consult a lawyer before making such a decision.

3.2. Federal Lobbying: IRS Guidelines

Lobbying on the federal level is governed by different rules than the state or local level. In the federal government, the U.S. Internal Revenue Service (IRS) – the federal agency responsible for administering and enforcing federal tax law – has detailed guidelines for legislative advocacy. The IRS distinguishes “lobbying” from “political activity”: lobbying is defined as “attempting to influence legislation” and political activity is defined as “directly or indirectly participating in, or intervening in, any political campaign on behalf of (or in opposition to) any candidate for elective public office.” The IRS defines these distinguished forms of legislative advocacy to better delineate who can engage in lobbying and political activity. For instance, organisations with 501(c)(3) status may engage in neither “substantial” lobbying activity or political activity without losing their tax-exempt status. However, organisations may hold educational meetings or create and distribute educational materials, which can be a form of legislative advocacy, without worrying about their tax-exempt status. If an organisation violates the IRS guidelines (by, for example, lobbying the federal government more than is permitted), they not only face losing their 501(c)(3) status, they can also face consequences like being taxed on the excess lobbying expenditures at a rate of 25%, which would have a significant effect on their finances. Depending on the form and manner of advocacy, your actions may implicate the IRS guidelines relating to legislative advocacy. Before engaging in any sort of legislative activity, make sure you understand, and are following, the IRS’s rules and regulations.

Although most bills filed in Congress never reach the committee stage of the lawmaking process, it is more than worthwhile to advocate for animals on the federal level. Federal legislative advocacy has the potential for wide impact, leading to substantial changes for nonhuman animals across the country. But before you do: (1) run a preemption check, (2) visit the IRS website and comply with their guidelines, and (3) research other related requirements for lobbying registration and reporting.

4. Legislative Advocacy in City & State Governments

Legislative advocacy encompasses attempts to “influence the introduction, enactment, or modification of legislation” – but what is legislation? Legislation typically refers to ordinances, resolutions, and statutes. Ordinances are local laws, while resolutions can be local, state, or federal laws, and statutes can be state or federal laws. Cities and States in the US have different legislative processes. The city of Portland, Oregon, and the State of Oregon will be used as examples of such processes in this section.

Ordinances are municipal laws enacted by city council members or equivalent elected officials. Ordinances serve the purpose of passing regulations that govern rules of conduct and determine legal rights and duties in local communities. For example, a 2019 ordinance enacted by the New York City council bans the sale of foie gras by penalising food purveyors that serve the dish in city limits. Alternatively, a resolution expresses a legislature’s opinion, will, or intent on a particular issue. Unlike ordinances, which generally have a waiting period before going into effect, resolutions become effective immediately upon voting. For example, in July 2021, council members in Berkeley, California adopted a resolution to allocate half of the city’s expenditures of animal-based foods to plant-based products by 2024.

City codes can clarify how ordinances and resolutions in a city are passed. For example in Portland, every ordinance (except for emergency ordinances) must have two public readings, three affirmative votes, and a minimum of five days between introduction of the proposed ordinance and its final passage (Portland, Or., Ordinances, Passage, 2-120 (2022); Portland, Or., Rules of the Council, 3.02.040 (2022)). The enacted ordinance will go into effect thirty days after it is passed by the city council. Proposed resolutions also need three affirmative votes to pass, but only need one public reading (Portland, Or., Rules of the Council, 3.02.040 (2022). After the first reading of either a proposed ordinance or resolution, members of the public may testify in front of the Portland city council as to how they think the council should vote. From there, the second reading takes place, and the council members vote to either pass or reject the ordinance or resolution.

Statutes are on the state and federal level what ordinances are on the local level, but the process of how a bill becomes a statute is often more complicated than that of ordinance or resolution passage. Legislative sessions, when the proposing and enacting or rejecting of bills happens, are not always consistent on the state level. Depending on the year, there might be fewer opportunities to pass a bill into law in your state. The Oregon Legislative Assembly is a prime example, with regular sessions consisting of 160-days of lawmaking on odd numbered years and 35-day short sessions taking place in even numbered years. While brainstorming an idea for a new bill, whether to create a new law or amend an existing one, be sure to research the state legislature’s calendar to confirm that the session is long enough to accommodate the legislative proposal.

Whether you are advocating on the state or federal level, making a legislative idea a reality requires first sharing it with one or more Senators or Representatives. First, find a legislator to sponsor the bill to get it introduced in either the House of Representatives or the Senate. When a Representative agrees to champion your idea, that Representative will submit a legislative draft request to the office of legislative counsel for a legislative draft of your proposed idea. Once the language is approved by sponsors and stakeholders, the legislative draft will be assigned a bill number and then it will receive a first reading. After the bill’s first reading in the House of Representatives, the bill will be assigned to a committee which reviews it, holds hearings to get expert, industry, and public opinion, and can host work sessions to better understand the issue at hand. The committee issues a report, and any associated amendments are printed with a new version of the bill. The bill then undergoes its second reading in the House of Representatives before being read for a third time and voted upon. If the bill passes by a majority in the House (thirty-one Representatives in Oregon), it is passed onto the Senate. The bill is read in the Senate for the first time, the Senate President assigns it to a committee, and the committee sends it back to the Senate for its second and third readings. If the bill is voted favourably by a majority of Senate members (sixteen Senators in Oregon), it is reported back to the House so that the Speaker of the House, the Senate President, and one other high-ranking official can sign it. From there, the enrolled bill lands on the Oregon Governor’s desk who has five days to sign it or veto it. If the bill is signed into Oregon state law, the bill’s effective date comes later – typically January 1 of the following year. Bills can start either in the House or Senate or proceed through both at the same time. Regardless of where it starts, both chambers need to agree on the final language before sending it a Governor for signature.

This long, drawn out legislative process means many bills will die in committee, or not even make it that far. However, working on even unsuccessful legislative campaigns is worthwhile. Statutes have power to promote justice, prevent harm, and shift how we treat nonhuman animals. Legislative efforts, whether enacted into law or not, contribute to raising awareness about animals in the Legislature. For that reason, although the legislative process can be cumbersome, advocating for change in the political institutions remains worthwhile.

5. Inclusive Outreach: Tribal Jurisdictions

“There is no practice of law that does not intersect with issues that are important to Native Americans and their sovereignty” (Interview with Dr. Carma Corcoran, Director of the Indian Law Program at Lewis & Clark Law School (Jan. 27, 2022) (Remote). No matter where animal advocates are located, it is of paramount importance to consider and include tribal nations and other affected and marginalised people. This section offers only a glimpse into how advocates can incorporate indigenous interests and rights into their legislative campaign, and we suggest advocates conduct further research to ensure that tribal communities play an active role in legislative advocacy efforts.

Indigenous tribes are considered domestic nations under federal law. These native communities possess self-governance independent from the U.S. government, albeit limited by treaties, Executive Orders, acts of Congress, court decisions, and other legal mechanisms. Tribal sovereignty ensures that indigenous communities have the power to create their own governments, enact and enforce civil and criminal laws, and regulate property and activities within their jurisdictions – including the use of natural resources. Many legislative efforts targeted towards protecting animals will impact the land, resources, or rights of indigenous people in some capacity. For example, animal advocates could champion a federal bill aimed at reducing access for wild-caught fishing. While the goal would be to minimise the suffering and death of fish and other aquatic life, an unintended result could be an infringement on tribal fishing rights. To avoid interfering with tribal sovereignty, and to buttress the political power of indigenous communities, communication with, and inclusion of native tribes in, the legislative planning process is imperative.

In the beginning stages of any legislative campaign, consider how advocacy might impact native tribes. This step includes identifying the indigenous nations in the region your bill covers and reaching out to these communities as soon as you have a grasp on how your bill may affect them. For instance, a coalition of animal advocates championing a federal bill aimed at reducing access for wild-caught fishing might want to adjust its jurisdiction solely to the state of Oregon. Because fishing is intricately tied to food, water, and land sovereignty, advocates should reach out to the nine tribes of Oregon —or at least the tribes that reside near and oversee the Columbia or Yakima Rivers. But before advocates get in touch with the tribes, they should research possible stakeholders, sociopolitical outcomes, and anticipated opposition.

In this instance, possible stakeholders include federal agencies like the Bonneville Power Administration, state agencies like the Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife, and nonprofits like Ecotrust or the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission. Government actors, nonprofit advocates, and other stakeholders have important perspectives to provide and roles to play in legislative campaigns. By outlining to the tribal liaison their intentions for relationship-building with these different actors, advocates allow the tribe to have more say over this political process. Advocates should also research how their proposed bill could impact tribal (and marginalised) communities and come up with possible solutions to nullify or mitigate any potential harm. Lastly, advocates should consider who might oppose their bill: government actors, industry players, or tribes themselves. Foreseeing imminent conflict is essential to take steps towards the conflict resolution necessary to ensure all parties—humans and animals—have their interests considered.

With their research collected and organised, the coalition can now contact the relevant tribes’ natural resource departments and tribal councils. If advocates do not know whether their bill could affect specific tribes, advocates should always err on the side of caution and contact them with their general legislative proposal and relevant concerns. If advocates are uncertain about the tribe's stance on the bill, they can politely ask if the tribal liaisons are willing to share their thoughts and emphasise that they want to work with the tribe to ensure the bill benefits (or least does not impair) the tribal nation. If those advocates speak with have recommendations for doing further research or contacting other individuals, advocates should heed their advice. And perhaps most important, advocates should respect the tribe’s opinion of the bill.

* This section was written with the assistance of Dr. Carma Corcoran of the Chippewa-Cree tribe, Director of the Indian Law Program at Lewis & Clark Law School.

The nine tribes of Oregon are individual nations with diverse cultures and practices, meaning there is a strong chance tribes will have different standpoints when it comes to the progression of your legislative campaign. These political intricacies amongst the tribes does not mean advocates should simply listen to the tribe that agrees with their view, or falsely state that all nine tribes of Oregon support their bill when they do not. Rather, advocates should ask themselves whether this legislative advocacy is for the greater good, and make sure they have explored all options, and done everything they possibly can to optimise ethical outcomes and minimise potential harms. Although challenging, incorporating human interests into your calculus and determining whether an idea is optimal for all, contributes to fostering responsible animal advocacy.

Throughout the entire process of generating a legislative concept, conducting sufficient research, communicating with tribal nations, and assessing appropriate outcomes, advocates must keep in mind that culturally, spiritually, and politically speaking, native people have different perspectives than the western world on the environment and the beings that reside in it. Every step of the way, but especially in direct contact with tribes, non-native animal advocates must be respectful of those differences and properly reflect on their biases. If your worldview is westernised and you believe that it is superior to a native person’s value system, do not engage in conversation before sincerely reexamining why you feel that way. Take into consideration the historical, cultural, and sociopolitical factors that influence your ideology, and acknowledge that your worldview is not necessarily the only “right” one. Reflecting in this manner does not mean assuming your opinion is invalid or that the legislative campaign is not worth pursuing. Rather, it serves as an opportunity to learn about other cultures and nations and develop greater sensitivities to navigating a complex world and creating the opportunities to build true collaborative coalitions.

Author: Miranda Eisen, Student at the Animal Law Clinic, Lewis & Clark Law School (under the supervision of Professor Kathy Hessler)

Resources

Aditya Katewa, ‘Immensely Powerful’: Activists Laud City Decision to Commit to Plant-Based Food, The Daily Californian, (Feb. 21, 2022).

Animal Protection New Mexico, “Understanding the Differences Between Statutes, Regulations, Ordinances, and Common Law,” (last visited Feb. 20, 2022).

Autistic Self Advocacy Network, “Advocacy on a National Level: Influencing Federal Government and Policy,” (last visited Feb. 12, 2022).

Ballotpedia, “Mayor-Council Government,” (last visited Feb. 12, 2022).

Ballotpedia, “Open Town Meeting,” (last visited Feb. 12, 2022).

Bill Keating: U.S. Representative, “The Legislative Process,” (last visited Feb. 12, 2022).

Caleb Pershan, City Council Officially Voted to Ban Foie Gras, Eater N.Y. (Oct. 30, 2019).

ChangeLabSolutions, “Assessing & Addressing Preemption: A Toolkit for Local Policy Campaigns,” (Sept. 2020).

ChangeLabSolutions, “Fundamentals of Preemption,” (June 2019).

City of Portland, Or., “How Council Works,” (last visited Feb. 20, 2022).

City of Portland, Or., “What Exactly is an Ordinance?,” (Mar. 19, 2020, 8:32 AM).

Coalition of Or. Land Trusts, Lobbying for Land Trusts: A Guide to Lobbying Regulations for Nonprofit Organizations, (Sept. 2018).

Congress.gov, “How Our Laws are Made,” (last visited Feb. 12, 2022).

Duke Health, “Lobbying Definitions, Exceptions, Examples,” (last visited Feb. 12, 2022).

Georgetown UniversityLaw Center, “Which Court is Binding?,” The Writing Ctr. at Geo. Univ. L. Ctr, (2017).

Govtrack, “Oregon,” (last visited Feb. 12, 2022).

Internal Revenue Serv., The Restriction of Political Campaign Intervention by Section 501©(3) Tax-Exempt Organizations, (last visited Feb. 12, 2022).

Jason Gordon, Role of the Judiciary in the Legal System, The Business Professor, (June 23, 2021).

Legal Info. Inst., Cornell Law School, “American Indian Law," (last visited Jan. 30, 2022).

Mich. Municipal League, “Work Sessions – Use by Legislative Bodies,” (last visited Feb. 21, 2022);

Municipal Res. & Serv. Ct. of Wa. Taking Action Using Ordinances, Resolutions, Motions, and Proclamations, (Feb. 20, 2020).

Nat’l League of Cities, Cities 101—Types of Local US Governments, (last visited Feb. 12, 2022).

Or. Blue Book, “About Oregon’s Legislative Assembly,” (last visited Feb. 20, 2022).

Or. Coal. of Local Health Officials2021 Legislative Toolkit, (Jan. 2021).

Or. State Legislature, “How Ideas Become Law,” (last visited Feb. 20, 2022).

Oregon.Gov, “Overview of the Nine Tribes,” (last visited Jan. 30, 2022).

Prosperity Now, “Federal Legislative Process,” (last visited Feb. 12, 2022).

Texas Coalition to Abolish Death Penalty, Advocacy 101, Citizen Action Guide, (2010).

The White House, “State and Local Governments,” (last visited Feb. 12, 2022).

The White House, “The Executive Branch,” (last visited Feb. 12, 2022)

The White House, “The Judicial Branch,” (last visited Feb. 12, 2022).

Thomas Nussbaum & Chris Micheli, From the Classroom: Looking at the Offices of Governor, President, Capitol Weekly, (May 27, 2015).

Tom Carper: U.S. Senator for Delaware, “How a Bill Becomes a Law,” (last visited Feb. 12, 2022).

U.S. Capitol Visitor Center, “Two Bodies, One Branch,” (last visited Feb. 12, 2022).

U.S. Courts, “Comparing Federal & State Courts,” (last visited Feb. 13, 2022).

U.S. Courts, “Court Role and Structure,” (last visited Feb. 12, 2022).

U.S. Dept. of the Interior: Indian Affairs, “Frequently Asked Questions,” (last visited Jan. 30, 2022).

U.S. House of Representatives, “Branches of Government,” (last visited Feb. 12, 2022).

USAGov, Internal Service Revenue, (last visited Feb. 12, 2022).

USAGov, “How Laws are Made and How to Research Them,” (last visited Feb. 12, 2022).

UsaGov, “How Laws are Made and How to Research Them,” (last updated Feb. 8, 2022).

USHistory.org, “How a Bill Becomes a Law,” (last visited Feb. 20, 2022).

USLegal, Ordinances, Resolutions, and Other Legislation, (last visited Feb. 20, 2022).

Wildlife Soc’y The State & Federal Legislative Process and How You Can Become Involved, (June 15, 2020).

World Population Review, “Number of Representatives by State 2022,” (last visited Feb. 12, 2022).