1. Competence of the EU in Regulating Animal Welfare

The EU is an international legal system to which 27 countries adhere to – the EU Member States. By way of a series of treaties binding the EU Member States, these 27 countries have transferred power to enact and implement legislation to the EU in a certain number of fields of law. Such a mandate to legislate is limited, meaning that the EU can only adopt legislation in these fields for which the Member States have agreed to transfer their power.

In their mandate to the EU, Member States have not allowed the EU to legislate on animal welfare. However, Member States have agreed that EU law should recognise animals as sentient beings and require that the EU and the Member States take into account their welfare in certain policy fields, including agriculture and fisheries. Specifically, article 13 of the the EU Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), which serves as one of the EU’s constitutional treaties, states:

“In formulating and implementing the Union's agriculture, fisheries, transport, internal market, research and technological development and space policies, the Union and the Member States shall, since animals are sentient beings, pay full regard to the welfare requirements of animals, while respecting the legislative or administrative provisions and customs of the Member States relating in particular to religious rites, cultural traditions and regional heritage.”

The duty to take into account animal welfare in EU and national laws and policies includes one exemption: cultural and traditional practices. Practices such as bullfighting, cockfighting, or slaughter without stunning for religious purposes are considered cultural and traditional practices.

Another significant limitation of Article 13, TFEU is that such a provision does not explicitly allow the EU to regulate the treatment of farmed animals; but instead merely requires the EU to take into account the welfare of animals. In other words, the TFEU does not create a “competence” for the EU to enact legislation in the field of animal welfare.

The Court of Justice of the European Union, which is tasked with interpreting EU law (see section below), confirmed the EU’s lack of competence in enacting legislation related to animal welfare in several cases, in 1986, 2001, and 2017.

Despite this limitation, the EU Institutions have provided common standards on farm animal welfare. This legislation was adopted on the EU’s competence in enacting common standards in agricultural production, on the basis that differentiated rules across EU countries might create unfair competition for businesses involved in the production of animal-source products – a phenomenon commonly referred to as “unlevel playing field.”

2. National Advocacy Efforts versus EU Advocacy Efforts

When it comes to farm animal welfare standards, EU law only sets minimum standards. Unlike other fields of legislation and policies, such as the welfare of animals used for scientific purposes, EU Member States are thus able to adopt, in their national legislation, farm animal welfare standards that go above and beyond those set in EU law. As a result, animal advocates can either try and influence their national governments to pass higher standards in a given country, or the EU, to pass higher standards that would apply in all 27 Member States.

In practice though, many member states have adopted only a few farm animal welfare standards superior to EU minimum standards. The reluctance of Member States to adopt higher standards can be partly explained by the fact that the EU is a free trade area, wherein products can be produced and sold across Member States, as well as the political power of industrial farm animal production groups. As a result, Member States that have adopted higher standards than EU law are not able to ban the sale of products from Member States that have chosen to abide by the EU’s minimum animal welfare standards.

For example, Austrian law prohibits the use of cages in egg production. However, Austria remains obligated to sell eggs from caged hens from other countries that only abide by minimum EU legal standards, and in doing so, still allow the use of cages – such as Italy or France.

Because higher farm animal welfare standards entail higher production costs, Member States typically refrain from adopting farm animal welfare standards that are superior to EU minimum standards. Specifically, Member States generally do not impose higher standards to their domestic producers by fear of putting them at a competitive disadvantage with cheaper imports.

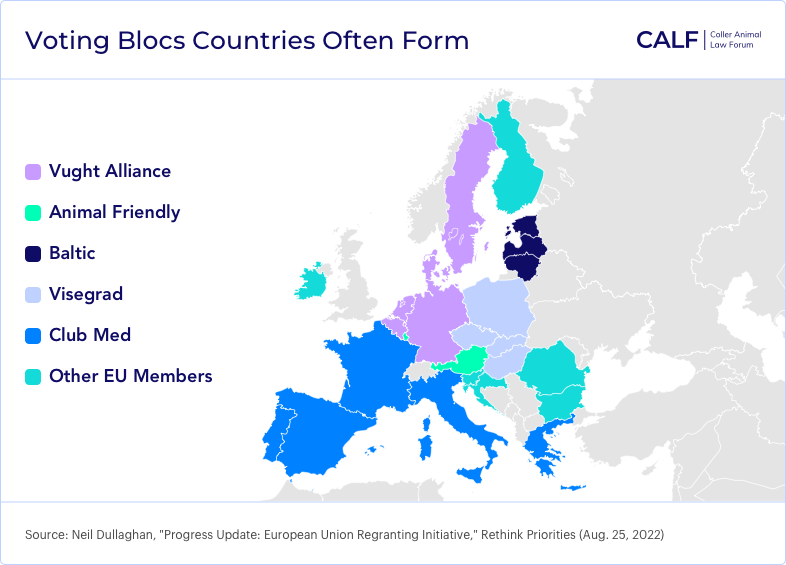

Despite the existence of a chilling effect in passing progressive national farm animal welfare laws, some countries have adopted higher standards than these minimum standards set in EU law. Such in the case for Austria, Germany, and Czechia, which all ban the use of cages for egg-laying hens, when such a use is allowed in EU law. Similarly, Sweden, Finland, and Lithuania prohibit tail docking on pigs, although this practice is not prohibited by EU law. Sweden also prohibits the use of gestation and farrowing crates for sows, a measure also above and beyond EU law. However, these cases are not common at the scale of the 27 Member States and only occur in countries where production levels of animal-source food tend to be negligible.

For this reason, the proper, most adequate level of governance to pass progressive legislation for farm animals remains the EU, as EU law applies uniformly in all 27 Member States, and neutralises the chilling effect caused by free movement of animal-source products on the EU market.

Yet, national efforts and corporate commitments can pave the way for efforts to be adopted at EU level. For instance, the upcoming ban on the use of cages in EU law was largely prompted by the transition away from cages in egg production on account of national bans in Austria, Germany, Luxembourg, and Czechia, as well as corporate commitments from major producers and manufacturers to only source eggs from cage-free systems.

National efforts also are crucial because Member States ultimately adopt EU legislation (see below, Council of the EU). It is therefore essential for advocates to secure Member States' support to the EU Legislature’s efforts to improve farm animal welfare in EU law. Some Member States in particular can have significant political influence in EU decision making, because they represent a large proportion of the EU population, or because their national industries are powerful at the scale of the EU. For example, in 2008, the EU decided to prohibit the use of individual crates for calves after the age of 8 weeks. The UK really pushed for this measure because British law banned the use of calf crates and this situation put British producers at a competitive advantage relative to other EU producers. Even though the UK was one of the only countries to have enacted such a ban, the UK managed to influence other Member States to agree to a limit on the use of crates, partly on account of pressure from the British veal industry on the UK government.

National advocacy efforts are also paramount in smaller countries of the EU. Less populated countries can also have influence by building coalitions with other smaller countries, and such coalitions are sometimes enough to create opposition to progressive legislation and lead to gridlock in the EU institutions.

3. The EU Institutions

The EU is composed of four main institutions:

- The European Commission: The European Commission acts as the executive branch of the EU by drafting laws and enforcing them. The European Commission is headquartered in Brussels, Belgium and is presided over by a president appointed by the Parliament every five years. The Parliament-appointed Commission president then appoints members of her cabinet, called Commissioners. The current President of the European Commission, serving a term from 2024 to 2029, is Ursula von der Leyen. The Commission president serves with 5 Vice-Presidents and 20 appointed Commissioners. Each commissioner heads an administration in different policy fields, called a “Directorate General.” These Directorate Generals are to the EU what ministries or departments are to national governments. The European Commission is often perceived by public affairs specialists as the most powerful of the EU institutions given it is the only institution that can propose legislation (see section 4.4.2.). When proposing legislation on the welfare of farmed animals, the European Commission relies on the expertise of its agencies, and particularly, the European Food Safety Agency (EFSA). The mission of the EFSA is to advise the EU Legislature on matters related to feed and food safety by providing scientific expertise on food safety, as well as animal welfare. Such scientific expertise is delivered under the form of “scientific opinion,” which are all publicly accessible. These scientific opinions do not have legal value and so the European Commission does not have to follow EFSA’s opinions. The EFSA’s scientific outputs are provided by experts who are external to the EFSA, and are distributed in panels dedicated to one area of expertise. There are 10 panels, including one on animal health and welfare, and the experts seating on these panels are organised in working groups. EFAs being an independent agency, it is not possible for advocates to contact experts and influence their scientific outputs. However, advocates can interact with the European Commission by encouraging the European Commission to seek advice to EFSA, or explain the reasons why the European Commission decided not to follow EFSA’s scientific opinions favourable to animals.

- The Council of the EU: The Council of the EU acts as the legislative branch of the EU, in conjunction with the European Parliament, by amending and voting on laws. Like the European Commission, The Council of the EU is also headquartered in Brussels, Belgium. The Council of the EU is composed of the ministers or heads of departments of its 27 Member States; The Council of the EU is presided over by a different Member State every six months – a process called a “rotating Presidency.” The Council of the EU is an altogether separate institution from the European Council, which gathers all the heads of EU Member States (Presidents, Prime Ministers, Chancellors, etc.) to shape EU law and policy.

EU Rotating Presidency

| Year | Month | null | Country |

| 2022 | Jan-June | France | |

| 2022 | July-Dec | Czech Republic | |

| 2023 | Jan-June | Sweden | |

| 2023 | July-Dec | Spain | |

| 2024 | Jan-June | Belgium | |

| 2024 | July-Dec | Hungary | |

| 2025 | Jan-June | Poland | |

| 2025 | July-Dec | Denmark | |

| 2026 | Jan-June | Cyprus | |

| 2026 | July-Dec | Ireland | |

| 2027 | Jan-June | Lithuania | |

| 2027 | July-Dec | Greece | |

| 2028 | Jan-June | Italy | |

| 2028 | July-Dec | Latvia | |

| 2029 | Jan-June | Luxembourg | |

| 2029 | July-Dec | Netherlands | |

| 2030 | Jan-June | Slovakia | |

| 2030 | July-Dec | Malta |

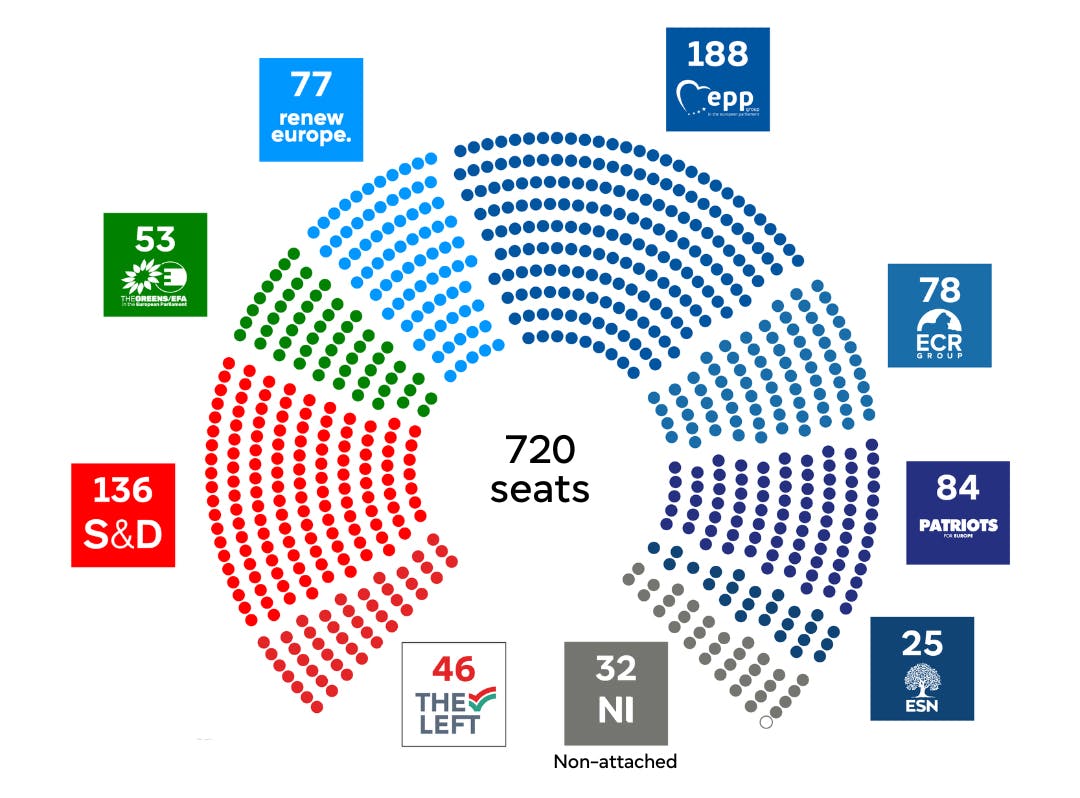

3. The European Parliament: Like the Council of the EU, the European Parliament also acts as a legislative branch of the EU by amending and voting upon laws. For this reason, the Council of the EU and the European Parliament are called “co-legislators.” The European Parliament is composed of 720 Members of the European Parliament (MEPs), elected in all 27 Member States every five years. The European Parliament has one president (currently, Roberta Metsola) and is divided into 22 committees tasked with amending and voting on laws. The Parliament is headquartered in Brussels, Belgium for committee meetings, and in Strasbourg, France for plenary sessions, during which MEPs all meet to vote on laws and resolutions. Committees that are relevant to farm animal welfare issues include the Committee on Agriculture.

4. The Court of Justice of the EU: The Court of Justice of the EU is the judiciary branch of the EU. It is located in Luxembourg City, Luxembourg and is composed of professional judges. The Court of Justice of the EU is tasked with interpreting EU law.

4. The EU Pre-Legislative, Legislative, and Post-Legislative Processes

4.1. The Pre-Legislative Phase

When the EU institutions have given no indication that they plan to adopt new laws, or amend existing ones, animal advocates can still aim to obtain legislative commitments from the EU institutions. Specifically, advocates can press for the EU institutions to offer commitments to include farm animal welfare objectives in future binding laws and regulations.

This phase of the process is called “pre-legislative process” because the EU institutions are not legally bound by such commitments, even though the institutions are more likely to implement measures from these commitments, due to their desire to be seen as keeping their word to the public. Because the pre-legislative process is of a political nature, rather than a legal one, the European Commission is not legally bound to follow a specific timeline or process until presenting a legislative proposal.

The commitments during the pre-legislative phase usually come under the form of official statements, publications (such as studies), or communications from the European Commission, addressed to the European Parliament and the Council of the EU. The European Parliament and the Council of the EU can also adopt resolutions, which are non-binding statements, that can be used to call the European Commission to take action.

One notable example of an influential policy document for farm animal welfare is the European Green Deal, which took the form of a Communication from the European Commission to the European Parliament and the Council of the EU. In the European Green Deal, the European Commission announced its intent to revise EU farm animal welfare legislation.

4.2. The EU Legislative Process

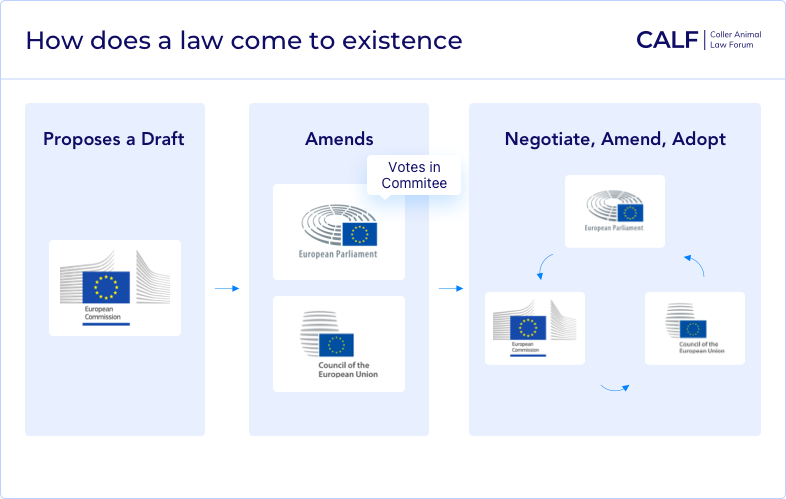

The legislative phase starts once the European Commission officially presents a proposal for legislation. The majority of EU laws that affect the treatment of farmed animals follow the “ordinary legislative procedure” as opposed to the “special legislative procedure,” which only applies to specific laws, such as laws approving international agreements.

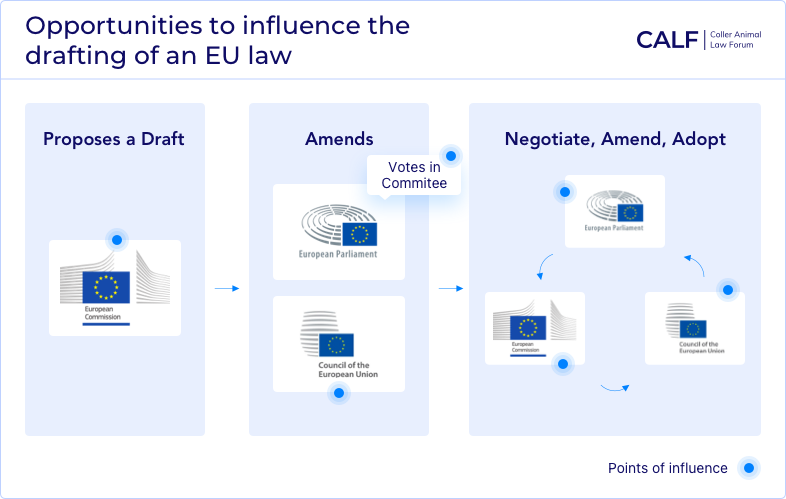

The ordinary legislative procedure follows several steps:

- The European Commission publishes a proposal for legislation. This proposal can either be an entirely new law or a law replacing an already-existing law – a process called “revision.”

- The European Parliament and the Council of the EU amends the European Commission’s law proposal. These amendments typically take the form of “reports” drafted and voted upon by the competent committee in the European Parliament, and the reports are then adopted in the Parliament’s plenary session in Strasbourg. The Council of the EU also composes and adopts its own reports.

- All three institutions (The European Commission, The European Parliament, and The Council of the EU) meet and negotiate to finalise the drafting of the law during a series of meetings called “trilogues.”

- The European Parliament and the Council of the EU vote to enact the law.

The ordinary legislative process usually takes several years to complete. For instance, the European Commission’s proposal for Directive 98/58/EC concerning the protection of animals kept for farming purposes was published in 1992, and adopted six years later, in 1998 (the main measures of the legislation entered into force as late as 2012).

A central element to keep in mind when working in EU public affairs is that, unlike most national jurisdictions, only the executive branch – the European Commission – can propose legislation. The Council of the EU and the European Parliament, which comprise the legislative branch, can only amend the laws proposed by the European Commission. Furthermore, the European Commission is responsible for the drafting and the adoption of implementing acts and delegated acts, which are the equivalent of decrees (also often called rules, or regulations) at national level. Implementing and delegated acts specify how to implement a given law.

4.3. The Post-Legislative Phase

The work of animal advocates does not stop at the adoption of the legislative act. Animal advocates have opportunities to influence the lawmaking process by ensuring that the legislation produces its intended effects. This type of activity comprises the post-legislative phase.

Once the European Parliament and the Council of the EU have adopted a legislative act, this act must be:

- Implemented: The European Commission must adopt a series of administrative acts (implementing and deleted acts) that specify the ways in which the legislative act should be implemented. Member States must also implement EU law into their national law, either by way of adopting new legislation, or administrative acts.

- And enforced: The European Commission and the Member States have a duty to ensure the legislative act is properly enforced.

Member States have sometimes failed to implement EU law within the period set in the EU law. In such cases, EU law allows the European Commission to start a procedure asking Member States to diligently implement EU law (called an “infringement procedure”). If the Member States refuse to comply, the European Commission can ultimately sue the Member States before the Court of Justice of the European Union’ (CJEU). The European Commission at one time launched infringement procedures against Italy for failing to implement into national law the mandatory stunning of animals prior to their killing, as required by EU law; the Commission also filed infringement procedures against Greece in 2014, for failing to implement the prohibition on the use of enriched battery cages after the transition period set by the EU. These two infringement procedures ended up before the CJEU, which ruled against Italy and Greece.

Infringement procedures can be an effective tool to ensure that Member States enforce EU law as well, provided the European Commission decides to make use of it. In case the European Commission is reluctant to sue Member States for not properly enforcing EU law, advocates can turn to other types of litigation, before national or EU courts, or engage in other types of advocacy, such as meeting with national administrations, to improve the compliance rate with EU law.

5. How to Engage with the EU Institutions

5.1. Traditional Ways of Engaging with the Legislature

Registration in the EU Transparency Register

As per EU rules, every person engaging in legislative advocacy must register in the EU Transparency Register. Legislative advocacy is defined as any “activities carried out by interest representatives with the objective of influencing the formulation or implementation of policy or legislation, or the decision-making processes of the signatory institutions or other Union institutions, bodies, offices and agencies [...]. Covered activities [...] include inter alia: “(a) organising or participating in meetings, conferences or events, as well as engaging in any similar contacts with Union institutions; (b) contributing to or participating in consultations, hearings or other similar initiatives; (c) organising communication campaigns, platforms, networks and grassroots initiatives; (d) preparing or commissioning policy and position papers, amendments, opinion polls and surveys, open letters and other communication or information material, and commissioning and carrying out research.” (Article 3, Interinstitutional Agreement of 20 May 2021 between the European Parliament, the Council of the European Union and the European Commission on a Mandatory Transparency Register, 2021 OJ (L 207) 1–17.)

Any organisation can register in the EU Transparency Register, provided they declare certain information, such as the number of the organisation’s staff, estimated amount of funding, and main funding sources. After they have registered, organisations are given an Transparency Register number, and EU rules advise that individuals belonging to a registered organisation provide such a number in all their written communications with EU officials.

Generic Ways

Each stage of the legislative process represents an opportunity to influence decision making taking place in all three institutions. For instance, animal advocates will have an interest in engaging with Members of the European Parliament and with the administration of the Member States at national level to try to amend the European Commission’s legislation proposal in a way that benefits animals. Similarly, animal advocates will have an interest in persuading all three institutions to safeguard progressive measures, or to eliminate less progressive measures, for farm animals during the trilogue phase.

This type of engagement can take many forms: meeting with policymakers, campaigning, sending official letters, holding events, etc.

Public Consultations

All documents published by the European Commission during the pre-legislative phase are also submitted to an online public consultation, in which the European Commission collects feedback from EU citizens, industry representatives, and NGOs. The list of ongoing public consultations is available online.

When conducting studies, the European Commission will also enlist private consultancies to interview all stakeholders, including NGOs. The selection process is at the discretion of the consultancies conducting these studies, but consultants tend to interview a wide range of NGOs working to influence the EU.

Lastly, the European Commission created an official forum in 2017, which gathers representatives from industry, academia, and NGOs to further structure the public consultation process on animal welfare issues. This official forum is called the “Platform on Animal Welfare.” Any animal protection organisations can apply to be represented at the Platform on Animal Welfare, although the European Commission tends to select federations or organisations that operate at EU level. The Platform is divided into working groups and sub-working groups that adopt official statements (“position papers”). These statements have no legal value and simply inform the European Commission in setting policy goals. It is difficult to evaluate the efficiency of the Platform on Animal Welfare in obtaining progressive reforms for farm animal welfare because the industry is also represented within that platform, and so the positions by the Platform tend to be accommodating to industry interests. For this reason, calls for progressive measures so far have all originated from outside the Platform.

5.2. Other Ways of Engaging with the Legislature

5.2.1. The European Citizens’ Initiative

The European Citizens’ Initiative (ECI) is a mechanism enabling citizens to officially petition the EU’s executive branch, the European Commission, to enact legislation on a matter within its competence. The ECI has existed since the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty in 2009 to increase direct democracy. It is provided by the Treaty on European Union (TEU) in its article 11(4), as follows:

Not less than one million citizens who are nationals of a significant number of Member States may take the initiative of inviting the European Commission, within the framework of its powers, to submit any appropriate proposal on matters where citizens consider that a legal act of the Union is required for the purpose of implementing the Treaties.

The requirements to submit an ECI are detailed in Regulation (EU) 2019/7881 (the ECI Regulation). For an ECI to be valid, it must gather the signatures of:

- At least one million EU citizens who are at least of the age to be entitled to vote in elections to the European Parliament ;

- From at least one quarter of the EU Member States ;

- And in at least one quarter of the EU Member States, the number of signatories must be at least equal to the minimum number set out in Annex 1 of the ECI Regulation. Such a number corresponds to the number of the Members of the European Parliament elected in each Member State, multiplied by the total number of Members of the European Parliament, at the time of registration of the initiative.

Additionally, an ECI must be submitted by seven citizens coming from at least seven EU Member States, although the ECI can be supported and advertised by an organisation. Only an ECI whose registration was accepted by the European Commission can go forward.

Even in the cases where an ECI gathered enough signatures, the European Commission is not required to implement the request formulated in the ECI. The ECI is merely a mechanism to ask the European Commission to adopt legislation. Thus, the success of an ECI is not measured by its number of signatures, but by the implementation of the request it formulated to the European Commission.

Process

Once a proposed ECI is submitted on the European Commission’s portal, the supporters of the ECI have 12 months to collect the number of signatures required, starting from the date of their own choosing. Being an official petition, the signatory must provide a document of identification when submitting their signature.

Once the proponents of an ECI have gathered the minimum amount of signatures, the organisers submit the ECI signatures to the Member States so they can certify the signatures (within three months), after which the signatures can be submitted to the European Commission, which then organises, within three months, a hearing at the European Parliament with the ECI organisers. Finally, the European Commission answers by providing “its legal and political conclusions on the initiative, the action it intends to take, if any, and its reasons for taking or not taking action” as per Regulation 2019/788.

A Short History of ECIs in the EU

Since the creation of the ECI in 2007, 110 ECIs have been submitted for registration, 85 of which have completed registration on the European Commission’s ECI portal, including six on animal protection issues (“Save Cruelty Free Cosmetics”, “End the Cage Age,” “Stop Vivisection,” “Save the Bees,” “Stop Finning – Stop the Trade,” “EU Directive on Cow Welfare”). The European Commission usually rejects a registration on account that such a registration does not comply with the rules set out in the ECI Regulation or addresses an issue that does not fall under EU competence.

Of the 85 registered ECIs, only seven have reached the sufficient number of signatures, including two on animal protection issues, the “Stop Vivisection” and the “End the Cage Age” ECIs. The European Commission only followed up on one ECI, though the Commission undertook legislative actions in two cases out of six. In 2021, the European Commission announced it would take legislative action to end the use of cages in a response to the “End the Cage Age” ECI.

In the majority of cases so far, the European Commission responded to an ECI by proposing a series of non-legislative follow-up actions. This has been the case for the 2015 “Stop Vivisection” ECI, where the European Commission simply committed to better implementation of existing legislation, considering that the request formulated in the ECI had already been addressed through EU legislation.

5.2.2. Litigation

Advocates who wish to improve the welfare of farmed animals might also turn to the courts and engage in strategic litigation.

Opportunities to litigate at Member State level differ considerably from country to country, and so advocates contemplating litigation in their country usually consult with a lawyer in their jurisdictions.

At EU level, advocates can initiate proceedings before the European Court of Justice (ECJ), which is the judiciary branch of the EU. The primary role of the ECJ is to interpret EU law to ensure it is applied consistently across all the 27 Member States.

There are different types of actions possible before the ECJ. Advocates do not always have standing (i.e. they do not have the right to file a lawsuit) to litigate before the ECJ, but they can try and influence their governments or the European Commission to bring cases before the ECJ:

Preliminary Rulings

This type of action is the most common before the ECJ and consists of one or several questions from a national court to the ECJ to ask for clarification on how an EU law should be interpreted, if a law is valid, and whether a national law or practice is compatible with an EU law. The opinion of the court takes the form of a ruling. ECJ rulings are binding for Member States in such domains where EU law takes precedence over national law.

Recent examples of preliminary rulings related to farm animal welfare include two cases regulating the slaughter of animals without stunning in Case C-336/19, Centraal Israëlitisch Consistorie van België e.a. and Others, 17 December 2020 and Case C-497/17, Oeuvre d’assistance aux bêtes d’abattoirs (OABA) v Ministre de l’Agriculture and Others, 26 February 2019.

Infringement Proceedings

An infringement proceeding is a type of case taken against a national government for failing to comply with EU law. Infringement proceedings can be initiated by the European Commission, or by another EU Member State. If the Court finds against the defendant, the defendant will be fined until it complies with EU law.

Recent examples of infringement proceedings related to farm animal welfare include C – 147/77, Commission of the European Communities v Italian Republic, 6 June 1978; C–339,/ 13, Commission v Italy, 22 May 2014, in which Italy failed to comply with EU law on the mandatory stunning of animals at slaughter and the legislation on the welfare of egg-laying hens.

Actions for Annulment

An action for annulment can be initiated by a citizen, an EU Member State, or any of the three EU institutions (European Parliament, the European Commission, and the Council of the EU) against the EU to challenge the enactment of a rule (usually a regulation or directive) adopted by an institution, body, office or agency of the EU.

There is only one example of an action for annulment brought by the UK against the Union to challenge the adoption of the EU legislation on egg-laying hen welfare in a 1986 case (C – 131/86, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland v Council of the European Communities, 23 February 1988).

Actions for Failure to Act

This type of action can be initiated by a citizen, a company, an EU Member State, or any of the three EU institutions (European Parliament, the European Commission, and the Council) against the EU institution’s inaction to enact rules after it has been called to act. There is no example of case law involving an action for failure to act related to farm animal welfare legislation.

The content of this section is derived from The European Institute for Animal Law & Policy, For a More Humane Union (2022), p. 23 - 24.

Author: Alice Di Concetto, Chief Legal Adviser, The European Institute for Animal Law & Policy

The author would like to thank Neil Dullaghan for his helpful feedback.

Resources

References

Katy Sowery, Sentient Beings and Tradable Products: The Curious Constitutional Status of Animals Under Union Law, Common Market Law Review, (2018).

Rasso Ludwig and Roderic O’Gorman, A Cock and Bull Story? – Problems with the Protection of Animal Welfare in EU Law and Some Proposed Solutions, Journal of Environmental Law, (2008).

Tara Camm and David Bowles, Animal Welfare and the Treaty of Rome – A Legal Analysis of the Protocol on Animal Welfare and Welfare Standards in the European Union, Journal of Environmental Law, (2000).

Neil Dullaghan, "Progress Update: European Union Regranting Initiative," Rethink Priorities (Aug. 25, 2022).

Further Readings

The European Institute for Animal Law & Policy, For a More Humane Union, (2022).